The Palatine Chapel in Palermo (Cappella Palatina)

Commenced by Roger II and consecrated in 1140. The Chapel is inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The Palatine Chapel is the royal chapel of the Norman kings of Kingdom of Sicily situated on the first floor at the center of the Norman Palace in Palermo. The chapel is a great symbol of multi-cultural cooperation. Craftsmen of three different religious traditions worked alongside each other.

The mosaics in Cappella Palatina

The Palatine Chapel, consecrated on Palm Sunday, 28 April, 1140, is inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The mosaics in the Palatine Chapel were probably made by the same craftsmen that made the mosaics in the Martorana and the central apse of the Cathedral in Cefalù.

The Chapel is part of the architectural complex of the Norman Palace. We don't know for certain when the mosaics were made, but the mosaics of the nave and aisles were most likely made during the rule of William I (1154-1166). William I (1120 or 1121 – May 7, 1166), called the Bad or the Wicked (Sicilian: Gugghiermu lu Malu), was the second King of Sicily, ruling from his father's death in 1154 to his own in 1166. He was the fourth son of Roger II and Elvira of Castile.

Christ Pantocrator in the sanctuary dome. Christ is surrounded by a host of archangels. According to Rodo Santoro (The Palatine Chapel and the Royal Palace, p. 43), an inscription at the base of the dome indicates that this mosaic was completed in 1143, whereas mosaics in the nave and aisles were completed between 1160 and 1170.

The ceiling

Look at this magnificent ceiling.

The wooden ceiling of star-shaped panels, carved and painted by 12th century craftsmen from Maghreb.

Star shaped panel with 8 points, framed with strips in Kufic script. Inside are petals with figures.

The magnificent wooden ceiling. Nave, north side.

Detail of the ceiling.

The mosaics in Cappella Palatina

The Chapel is dedicated to St. Peter.

The left lion mosaic in the Chapel is dedicated to St. Peter.

The right lion mosaic in the Chapel is dedicated to St. Peter.

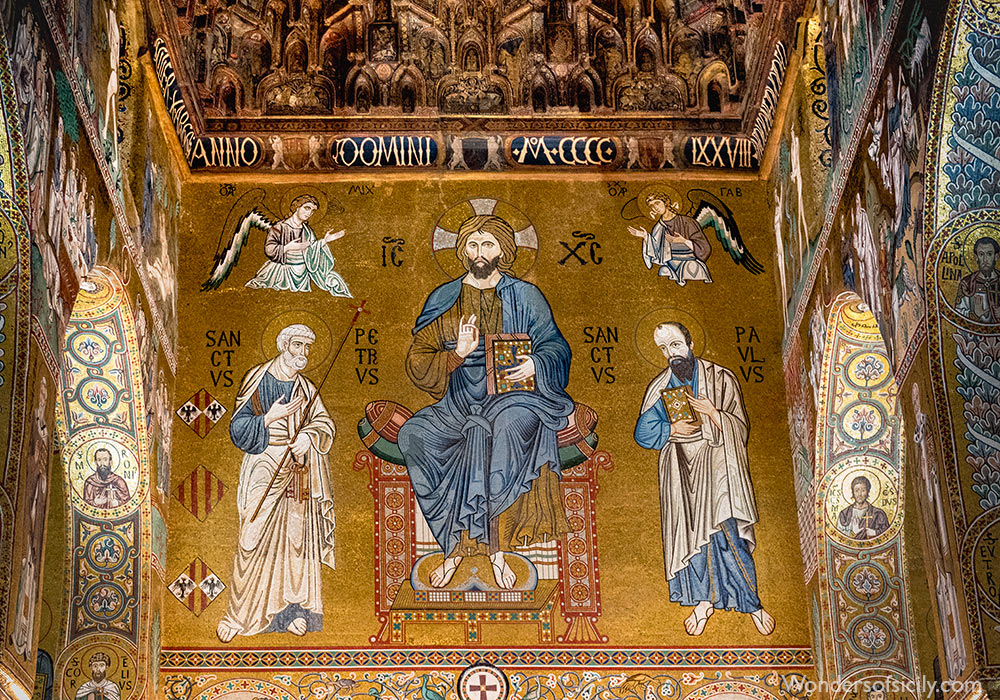

12th century mosaic on the western wall of the nave. Christ the Lawgiver seated on a lavishly decorated throne. To his left St. Peter; to his right St. Paul. Above are the Archangels Michael and Gabriel.

The madonna below Christ Pantocrator is an addition from the 18th century. Originally there was a window there.

Originally there were 50 windows (later blocked) designed to illuminate at all times of the day the stories told on the wall.

The texts in the chapel are written in Greek, Arabic and Latin.

The mosaics in the Palatine Chapel and the Church of the Martorana were probably made by the same craftsmen.

Saint Tiburtius (Tibvrcivs), a Christian legend beheaded c. 286.

The Byzantine mosaics has roots back to the first centuries of the Eastern Roman Empire. The best examples are to be found in Ravenna, Venice (St Mark's Basilica), Istanbul (Hagia Sophia), Monreale Cathedral, Cefalù Cathedral, Palermo (Church of the Martorana, Palatine Chapel).

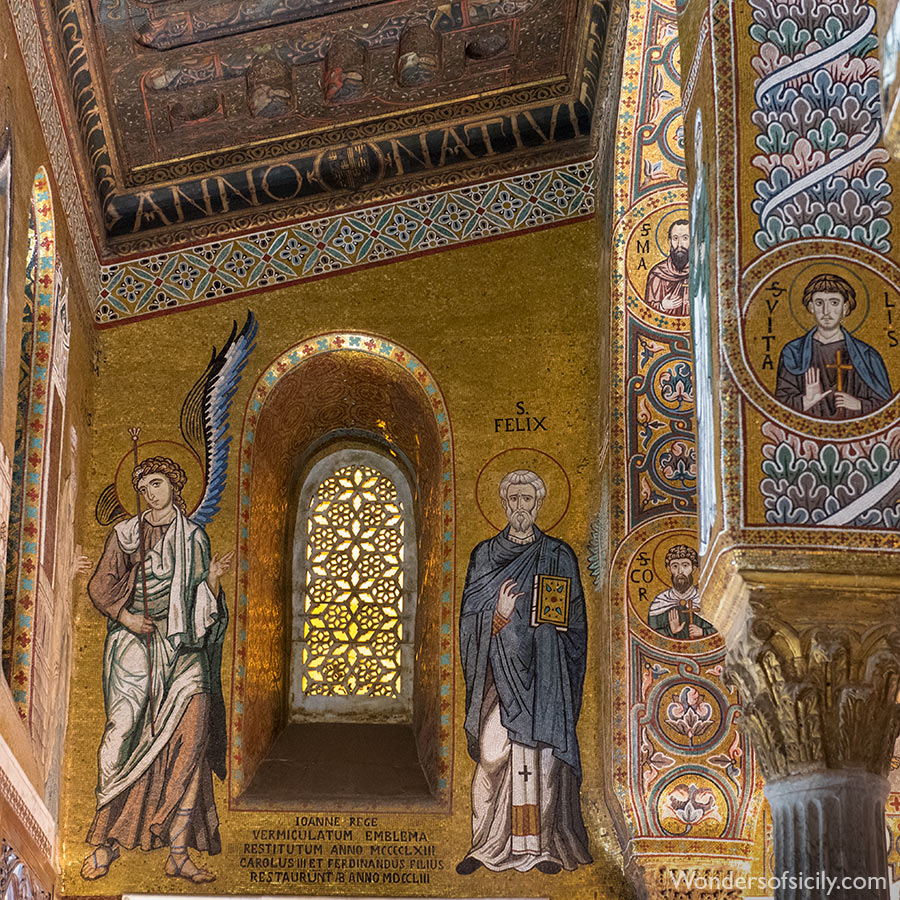

The text goes as follows: ‘ioanne rege vermiculatum emblema restitutum anno MCCCCLIII carolusinet ferdinandus filius restaurunt AB anno MDCCLIII’ (John the King restored the mosaic emblem in the year 1453. Charles and his son Ferdinand restored it again in the year 1753)

The Hetoimasia is a symbol that means “preparation (of the throne)” (of Christ the judge). The Hetoimasia consists of an empty throne and various symbolic objects, such as the crown of thorns, the dove, the spear, and the vinegar-soaked sponge.

Sculptural Elements

A sculptural detail of the Paschal Candelabrum in Cappella Palatina.

Detail of the Paschal Candelabrum in Cappella Palatina. The Paschal Candelabrum was carved by the "Master of the putti", who also made the capitals of the cloister in Monreale), according to Rodo Santoro.

Man being eaten by a lion. Detail of the Paschal Candelabrum ascribed to the Master of the putti, who also carved the capitals of the cloister in Monreale.

A sculptural detail of the Paschal Candelabrum.

Abstract ornaments

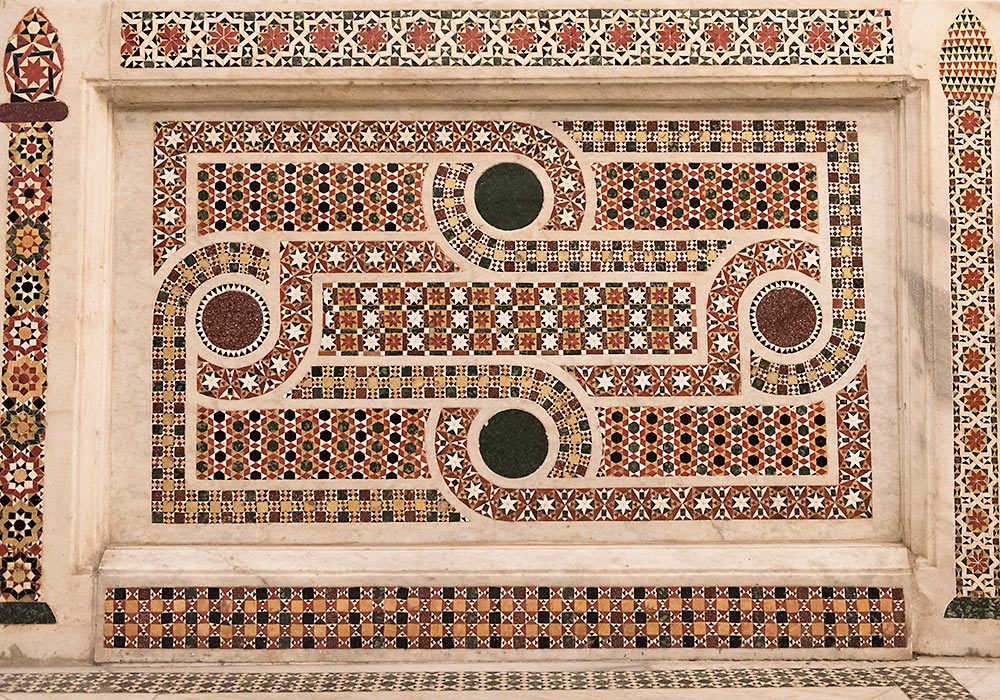

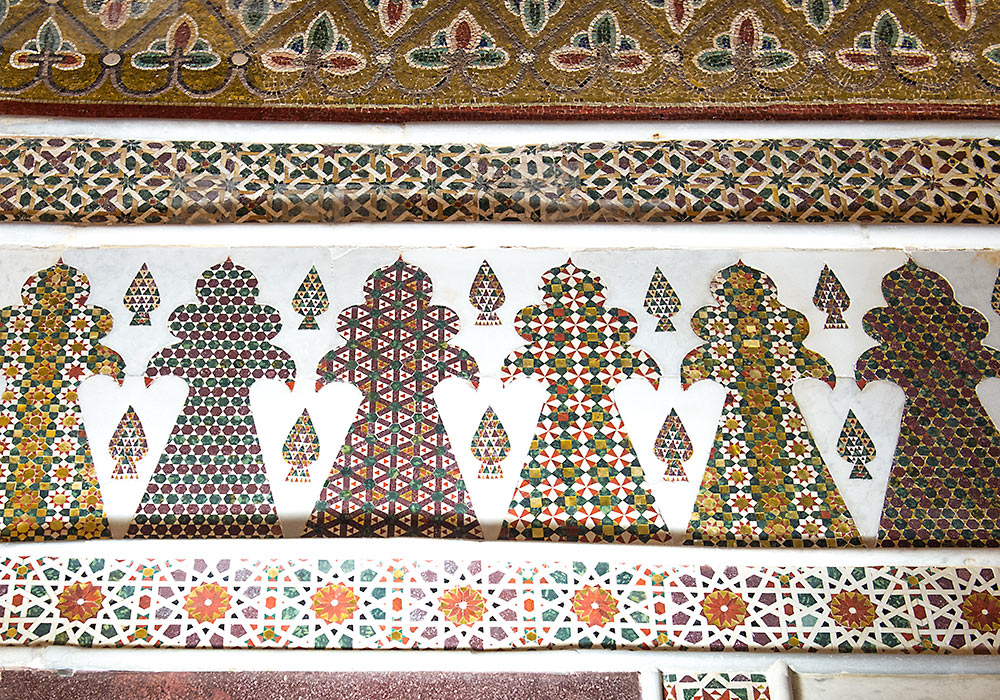

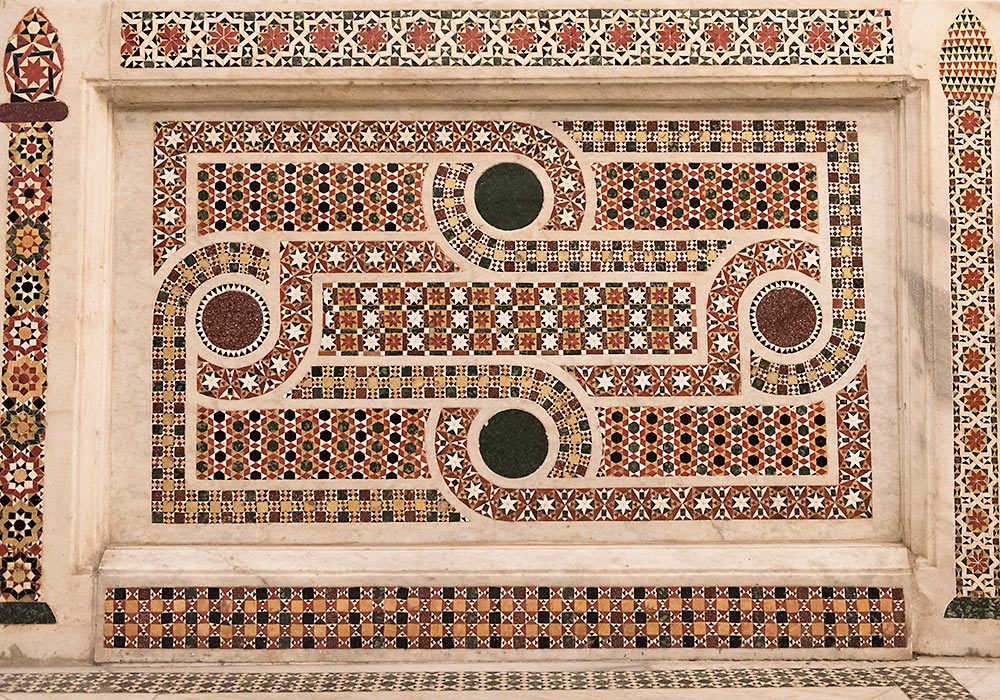

The Palatine Chapel: Detail of the wall.

Decoration on the wall.

Norman Monuments in Sicily (selection)

- Castelvetrano

The little 12th Century church of the SS. Trinità di Delia is, according to John Julius Norwich "the perfect fusion of Arab and Byzantine". [Link to the church on Google Maps] - Cefalù Cathedral

"Though much of the inside is now distressingly baroque, the outside is exquisite and the great apse mosaic the most sublime masterpiece Sicily has to offer."

After Norwich's book was written, the "distressingly baroque" elements have been removed. - Forza d'Agrò

The Basilian church SS. Pietro e Paolo is situated a few kilometres outside Forza d'Agrò. The inscription over the west door dates it to 1171-72. The church was built in the 560, then it was destroyed by the Arabs and it was rebuilt in the 1117. The church was restored by the architect Gherardo il Franco in the 1172 because of an earthquake. - Monreale

Cathedral and cloister

Castellaccio (12th Century) on the summit of Monte Caputo - Palermo

The Palatine Chapel (In the Royal Palace, also known as the Norman Palace)

Sala di Ruggero (In the Royal Palace)

S. Maria dell' Ammariglio (the Martorana)

S. Giovanni degli Eremiti

S. Spirito (the church known for the Sicilian Vespers in 1282)

The Royal tombs of Roger II, Henry VI, Constance and Frederick II (in the Palermo Cathedral / Duomo)

Source: John Julius Norwich: The Normans in Sicily: The Magnificent Story of "the other Norman Conquest

The term "Normans" (“men from the North”) applied first to the people of Scandinavia in general, and afterwards (Northmannus, Normannus, Normand) it is the name of the Viking colonists from Scandinavia who settled themselves in Gaul and founded Normandy. The Normans’ adopted a new religion (became Christians), a new language, a new system of law and society, new thoughts and feelings on all matters.

From their new home in northern France they set forth on new errands of conquest, chiefly in the British Islands and in southern Italy and Sicily.

If Britain and Sicily were the greatest fields of their enterprise, they were however very far from being the only fields. The same spirit of enterprise which brought the Northmen into Gaul seems to carry the Normans into every corner of the world. The conquest of England was made directly from Normandy, by the reigning duke, in a comparatively short time, while the conquest of Sicily grew out of the earlier and far more gradual conquest of Apulia and Calabria by private men, making their own fortunes and gathering round them followers from all quarters. They fought simply for their own hands, and took what they could by the right of the stronger.

They started with no such claim as Duke William put forth to justify his invasion of England; their only show of legal right was the papal grant of conquests that were already made. The conquest of Apulia, won bit by bit in many years of what we can only call freebooting, was not a national Norman enterprise like the conquest of England, and the settlement to which it led could not be a national Norman settlement in the same sense.

The Sicilian enterprise had in some respects another character. By the time it began the freebooters had grown into princes. Sicily was won by a duke of Apulia and a count of Sicily. Warfare in Sicily brought in higher motives and objects. Althought this was before the Crusades, the strife with the Muslims at once brought in the crusading element. Duke William was undisputed master of England at the end of five years; it took Count Roger thirty years to make himself undisputed master of Sicily. The one claimed an existing kingdom, and obtained full possession of it in a comparatively short time; the other formed for himself a dominion bit by bit, which rose to the rank of a kingdom.

Professor Robert Bartlett describes their exit like this in the excellent BBC documentary “The Normans”: “The Normans simply disappeared. This might sound like failure, but in fact it was the key to their success. They weren’t interested in the purity of their blood. They came, they saw, they conquered. Then they married the locals, learnt the language, and assimilated themselves out of existence.”

Links to more information about the Normans

- The Norman Conquest (Medievalsicily.com)

- Sicilian Peoples: The Normans by L. Mendola and V. Salerno (Bestofsicily.com)

- Tracing the Norman Rulers of Sicily by Louis Inturrisi (The New York Times)

UNESCO’s World Heritage List

Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalú and Monreale (Italy) - new on the list (2015)

Located on the northern coast of Sicily, Arab-Norman Palermo includes a series of nine civil and religious structures dating from the era of the Norman kingdom of Sicily (1130-1194): two palaces, three churches, a cathedral, a bridge, as well as the cathedrals of Cefalú and Monreale. Collectively, they are an example of a social-cultural syncretism between Western, Islamic and Byzantine cultures on the island which gave rise to new concepts of space, structure and decoration. They also bear testimony to the fruitful coexistence of people of different origins and religions (Muslim, Byzantine, Latin, Jewish, Lombard and French).

Palermo

- Palazzo dei Normanni (The Norman Palace)

- Cappella Palatina (The Palatine Chapel in the Norman Palace)

- Church of San Giovanni degli Eremiti

- Church of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio (also known as the Martorana)

- Church of San Cataldo

- Cathedral of Palermo

- The Zisa Palace (La Zisa)

- The Cuba Palace (La Cuba)

Norman Cathedrals

Cappella Palatina was used in an episode of the TV series Hannibal (an American psychological thriller–horror television).

Main sources

Rodo Santoro: The Palatine Chapel and Royal Palace (Palermo, 2013).

Blue Guide Sicily

Jean Paul Barreaud:

Docs, Reportages, Photos and Tours of Palermo.

Click here to book or read more!