Agrigento underground water channels and reservoirs, built by the Greek architect Phaiax (Phaeax) in the 5th century BC

The lion to the left of the church of the Purgatorio sleeps above the locked entrance to a huge labyrinth of underground water-channels and reservoirs, built by the Greek architect Phaiax in the 5th century BC.

Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad / Wonders of Sicily

The hypogeals of Agrigento, the ancient Greek city of Akragas , constitute a spectacular work of hydraulic engineering and hydrological catchment, entirely made with excavation. These tunnels were used as aqueduct network and allowed the economic and social development of the brightest city of the Magna Greece. Their development is predominantly linear with a roughly rectangular shape, dug into the rock, depth 20-30 m below the ground level.

At irregular distance, along the development of the tunnels, we can find wells (water holes) of circular shape used to catch the water. Each well has a ladder carved into the rock which obviously was used to go up to the ground level from there.

The largest and most extensive underground known today is the Hypogeal of Purgatory (Agrigento). This is the only case where the underground is developed by a complex path full of intersections, large rooms, creating an incredible maze effect.

The complex network of tunnels and wells today is partially inspected, because of the many collapses of rock that have partially or entirely occluded the gates but also because of human interventions, which in some cases preserved the right flowing of the waters and in other cases had to limit the unpleasant effects due to drainage.

The realization of this important and impressive structures under the city of Agrigento dates back to 480 A.C., when Agrigento and Syracuse defeated the Carthaginians (the battle of Himera), capturing prisoners who were enslaved. According to the sources, the prisoners were engaged in public works such as the construction of these aqueducts. "Most of these", Diodorus says, "were handed over to the state, and it was these men who quarried the stones of which not only the largest temples of the gods were constructed but also the underground conduits were built to lead off the waters from the city; these are so large that their construction is well worth seeing, although it is little thought of since they were built at slight expense. The builder in charge of these works, who bore the name of Phaeax, brought it about that, because of the fame of the construction, the underground conduits got the name "Phaeaces" from him." (Diodorus Siculus 25,11)

Another hypothesis is that they extended and integrated artifacts of an earlier period, perhaps belonged to the culture of Sicani. The Sicani (Sicanians) were a very ancient population in historical times who lived in the central and southern Sicily and the south-west. The Sicani were one of three ancient peoples of Sicily present at the time of Phoenician and Greek colonization. During the Iron Age their civilization it’s documented by necropolis and settlements located in the interior parts of Sicily. To Sicani culture is attributed the culture of Polizello - Sant'Angelo Muxaro, characterized by a typical ceramic painted in red and decorated with engraving.

Today the underground tunnels aren’t in a properly condition of conservation.

"Stability problems in Agrigento arise from both geological conditions and human actions. Agrigento still survives, although the natural erosion of the land has resulted in an incessant erosion of the cultural and historical heritage. Some intervention slowly taking place regarding the problem of the underground passages, such as the Purgatorio. [...] Similarly the visible deforestation and eventual destruction of the soil began in the sixteenth century when the area's population doubled. Growth pressure impelled the people to cut trees to expand agricultural land and provide building materials and fuel for cooking and warming. Erosion followed, which led to long-term soil destruction. By the end of the eigtheenth century, the Agrigentans had to import wheat. Between 1817 and 1847, they lost half of the nearby forest, which negatively affected the infiltration and retention of water, and caused further erosion of slopes."

(Dora P. Crouch: Geology and Settlement: Greco-Roman Patterns, 2004)

In this video Lillo Miccichè expresses the idea that before to restore the center of Agrigento it’s necessary to restore what it’s under the ground. He speaks about the precarious situation and geological risk for the safety of the city and its population.

You can see the entrance of the tunnel built in 1860 by the Government of the Borboni ( the same work made in Palermo for the grave of Porta d’Ossuna). Before this kind of realization the only entrance was made by ropes that went down from the surface. The wood beams dates back to 1966 after a landslide. The little stalactites aren’t made by pure water but made by anything comes from the surface, also sewer water. They asked for depuration, restoration, reinforcement but they have been ignored!

The iron beams were a good idea, according to Miccichè. He says that maybe they aren’t pretty but thanks to them the city, at the moment, is safe! At the end they say that the city is in danger…because the movement of the water never stop and could create problems to the soil layers.

In this video the geologist Giuseppe Lombardo is interviewed about the Hypogeum located under the Pirandello Theatre. It is still full of water. Visitors can see it during the “Festival of the almond tree” (Sagra del Mandorlo in Fiore), but not all the tunnels.

The reinforcement are made with tufa bricks, very durable. It’s safer than the Purgatory tunnels thanks to the shape of the tunnels. They are high but narrow so this is good from the static point of view.

Before the Theatre was built maybe there was a cave of tufa. During the War it was probably used as place of refuge from the bombings.

The only danger for the city of Agrigento, in this case, it’s due by debris blocking the water channels … so the water will find another way to flow away…

Sources

- The Encyclopaedia Britannica : a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information by Chisholm, Hugh, 1866- Published 1910-1922

- The Blue Guide Sicily

- Pietro Fattori (Teleacras)

- Diodorus Siculus 25,11

Coin from Agrigento (Akragas), circa 480-470 BC.

Description: Sicily, Akragas AR Didrachm. Circa 480-470 BC. Eagle with folded wings standing right, AKRA around / Crab, male head below, flanked by CΑ-Σ, all within shallow circular incuse. Jenkins group III-pl. 37, 18; SNG ANS-959. 8.37g, 21mm, 6h. Extremely Fine.

Source: Roma Numismatics Ltd (with permission)

Coin from Agrigento (Akragas), circa 460-446 BC.

Description: Sicily, Akragas AR Tetradrachm. Circa 460-446 BC. Sea eagle standing left on Ionic capital, AKRACANTOΣ around / Crab; spiralled tendril ornament with floral terminals below; all within shallow incuse circle. SNG ANS 982 var; Lee Group II; cf. SNG Lockett 695 for same obverse die, 696 for reverse type but different die. 17.54g, 25mm, 6h. Fleur De Coin.

From the James Howard Collection. Published in Roma Numismatics VII was the first of the Howard collection's two truly spectacular Akragas tetradrachms (lot 85), which bore an inverted dolphin as the reverse adjunct symbol. A comparison between these two exemplars of Akragantine coinage is extremely difficult, for both are of a quality that collectors have seldom, if ever, been offered the chance to acquire. Although this coin's reverse symbol may be considered somewhat less exotic than that of its abovementioned brother, the eagle's head is undeniably more detailed, and its plumage sharper - indicative of an overall slightly greater state of preservation. Indeed, the freshness of the metal and the lightly toned, satin finish are quite remarkable; this coin should certainly be considered to be amongst the very finest of its type.

Source: Roma Numismatics Ltd (with permission)

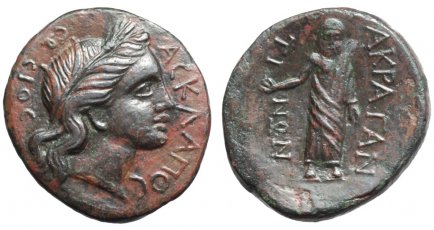

Coin from Agrigento (Akragas), Roman rule, after 210 BC.

Description: Sicily, Akragas Æ20. Roman rule, after 210 BC. Laureate head of Persephone right; ACKΛAΠOC to right, CΩCIOC to left / Asklepios standing facing, head left, holding patera in right hand; AKPAΓAN to right, TINΩN to left. SNG Copenhagen 123; SNG München 205; SNG ANS 1143; CNS I, p. 225, 144. 4.80g, 20mm, 6h.

Source: Roma Numismatics Ltd (with permission)

Coin from Agrigento (Akragas), circa 400-380 BC.

Description: Sicily, Akragas Æ Hemilitron. Circa 400-380 BC. Diademed head of river-god left, ΑΚΡΑΓΑΣ before / Eagle standing left on Ionic column, head right; crab to left, six pellets (mark of value) to right. CNS 89; SNG ANS 1097-1101. 18.50g, 26mm, 8h.

Near Extremely Fine.

Source: Roma Numismatics Ltd (with permission)

Agrigento Timeline

580 BC: Agrigento is founded, possibly on the site of an earlier Sicanian settlement, as a colony of Gela and came to prominence under the tyrants Phalaris and Theron

570–554 B.C.: Tyranny of Phalaris

Phalaris rules as tyrant, infamous for executing enemies in a brazen bull.

554 B.C.: Fall of Phalaris

Phalaris is overthrown; the subsequent form of government is uncertain.

488–473 B.C.: Tyranny of Theron

Theron reigns as tyrant, fostering the city's prosperity.

480 BC: The artificial lake Kolymbetra was dug by Theron's Carthaginian prisoners taken at Himera

472 B.C.: Establishment of Democracy

A democratic government replaces tyranny.

415–413 B.C.: Syracuse-Athens Conflict

Agrigento remains neutral during the Peloponnesian War.

406 BC: The Carthaginians capture the city after an eight-month siege and burn the city, marking the beginning of its decline.

340 BC: Agrigento was rebuilt by Timoleon, who defeated the Carthaginians.

289–279 B.C.: Rule of Phintias

Tyrant Phintias restores some of the city's former power.

261 B.C.: Roman Sack (First Punic War)

Romans sack Agrigento during the First Punic War.

255 BC: Carthaginians recapture the city

218-201 BC Agrigento suffered badly during the Second Punic War when both Rome and Carthage fought to control it.

210 BC: The Romans take the city again, this time Agrigentum remained in their possession until the fall of the empire. Agrigentum remained a largely Greek-speaking community for centuries after the Roman conquest.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the city successively passed into the hands of the Vandalic Kingdom, the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy and then the Byzantine Empire. During this period the inhabitants of Agrigentum largely abandoned the lower parts of the city and moved to the former acropolis, at the top of the hill (this was probably related to the destructive coastal raids of the Saracens).

Late 6th century: The Temple of Concord is converted into a church by the bishop of Agrigento, San Gregorio delle Rape (St Gregory of the Turnips)

828 AD: The Arabs take the city and make the trade flourish by cultivating cotton, sugar-cane and mulberries for the silk industry (they even had to make a new harbour, at Porto Empedocles)

1087: The Normans take Agrigento after a 116 days siege

By the end of the 18th century

The Agrigentans has to import wheat

1817–1847

Agrigento lost half of the nearby forest, which negatively affected the infiltration and retention of water, and caused further erosion of slopes.

1867

Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936) is born.

1885: The author Guy de Maupassant travels in Italy, Sicily included. After returning to Paris, Maupassant began publishing his Sicilian travel memoirs in installments in Le Figaro and Gil Blas

1927: Mussolini orders that the city should be called Agrigento, not Girgenti

1936: Luigi Pirandello dies

Sources: Wikipedia, The Blue Guide Sicily and various other sources