Museo Diocesano di Palermo (The Diocesan Museum)

The Diocesan Museum of Palermo, founded in 1927 by Cardinal Alessandro Lualdi, offers a rich journey through centuries of sacred art, history, and Sicilian identity. Located within the Archbishop’s Palace, the museum unfolds across 27 rooms along Via Bonello, spanning three floors and housing approximately 300 works of art—including paintings, sculptures, and decorative pieces—dating from the 12th to the 19th century. Thanks to careful restoration and adaptation, the museum provides a beautifully curated setting for exploring Palermo’s religious and artistic heritage. Visitors begin with medieval masterpieces from the Norman and Swabian periods and continue through the centuries, encountering gold-ground paintings, rare parchment works, frescoes, Renaissance sculpture by the Gagini family, and Baroque stucco by Giacomo Serpotta. Highlights include the evocative “Madonna of the Pearl,” 15th-century wooden crosses, and fragments from Palermo Cathedral, as well as rooms dedicated to Pietro Novelli and views of the city by Mario Di Laurito. From archaeological finds to intricate marble reliefs and expressive stuccoes, the museum tells a layered story of faith, artistry, and devotion in Palermo’s ecclesiastical life.

Madonna dell'Itria, 15th century fresco now in the Diocesan Museum in Palermo. Once located in the Church of the Madonna dell’Itria, also known as the Church of the Madonna della Pinta, commonly referred to as La Pinta. The nickname La Pinta likely originates from the Italian word pinta, meaning ‘painted,’ referencing the church’s notable decorative paintings. The church was originally founded in the 6th century and underwent several reconstructions over the centuries. In the 17th century, due to urban development, the original structure was demolished, and the associated confraternity relocated to a new church, which retained the name della Pinta.

“Itria” comes from the Greek word “Hodegetria” (Οδηγήτρια), which means “She who shows the way.” Hodegetria is a specific type of iconography in Byzantine art where the Virgin Mary is depicted pointing to the Christ Child she holds, indicating that he is “the Way” (cf. John 14:6 – “I am the way, the truth, and the life”).

“Madonna dell'Itria” roughly means “Our Lady of Hodegetria”. This name and devotion are especially common in southern Italy and Sicily, where Byzantine influence was historically strong.

The Coronation of the Virgin with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas of Bari. Tempera on wood, 1419. Once in the Church of San Nicolò lo Reale, Palermo. The text on John the Baptist’s roll is (most likely) “Ecce agnus Dei, ecce qui tollis peccata mundi” (with an abbreviation for agn[us]. The letters in the open book Saint Nicholas is holding may say something like “I am called Nicholas, the holy one / [servant] of the holy virgin.”

Detail of the painting above. Angels playing during the Coronation of the Virgin. Tempera on wood, 1419. Once in the Church of San Nicolò lo Reale, Palermo, now housed in the Diocesan Museum of Palermo (Museo Diocesano di Palermo).

“Madonna in Prayer.” Mosaic, 12th century. Originally from Palermo Cathedral.

Masonna di Loreto. Forgylt marmor, begynnelsen av 1500-tallet.

The walls of this room – Cappella Borremans – is entirely covered by a cycle of frescoes commissioned from the Flemish painter Guglielmo Borremans (circa 1672–1744) by Archbishop Matteo Basile (1731–1736), whose coat of arms is present on the short walls of the room. The scenes were painted around 1733–1734 and depict Stories from the Childhood of Christ, including, in clockwise order: the Adoration of the Magi, the Flight into Egypt, the Adoration of the Shepherds, and the Dream of Joseph, along with eight Prophets. The painted wooden ceiling dates from the same period. Around the mid-20th century, Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini, Archbishop of Palermo (1945–1967), converted the hall into a chapel by installing an 18th-century altar from the church of San Giovanni dell’Orfione. He placed his coat of arms beneath the Adoration of the Magi. The Baroque altar table features a tabernacle decorated with gilded copper and precious hardstones, including lapis lazuli, agate jasper, and amethyst. Among the furnishings are a pair of torch-bearing wooden angels from the mid-18th century, originally from the church of Santa Maria degli Agonizzanti in Palermo, and a pair of large candelabra in gilded wood from the third quarter of the 18th century, from the church of San Nicolò di Tolentino. On the altar are two decommissioned candelabra from the Oratory of San Vito in Palermo, once used in Romanian Orthodox worship, as well as two antique presidential chairs — one Rococo from the third quarter of the 18th century, and the other late 19th-century Neoclassical. One side of the chapel features a marble portal, probably of medieval origin, which in the 15th century connected the Archbishop’s Palace with the presbytery of the Cathedral. This allowed the Archbishop to reach the liturgical area quickly and securely, without exiting the building.

In Sicily, Guglielmo Borremans received numerous commissions to decorate both ecclesiastical buildings and the palaces of prominent individuals. In addition to large-scale fresco cycles, he also produced a significant number of easel paintings. The volume and distribution of his work suggest that he operated a sizable workshop.[8] His activity extended beyond Palermo to several other locations across Sicily, including Nicosia, Catania, Enna, Caltanissetta, Buccheri, Caccamo, and Alcamo.

One of his most ambitious undertakings was the decoration of the Chiesa di San Ranieri e dei Santi Quaranta Martiri Pisani in Palermo, a project he began in 1725. In this church, he employed extensive gilding and stucco work to produce one of the most opulent Baroque interiors in Sicily. This is also the only known work that bears his signature referencing his place of origin: Guglielmus Borremans Antuerpiensis Pinxit (“Painted by Willem Borremans of Antwerp”).

In 1733–34, Borremans painted several rooms in the Archbishop’s Palace in Palermo, some of which remain partially preserved. In addition to his ecclesiastical commissions, he participated in various secular decorative programs, including the ceiling frescoes in the main gallery of the Palazzo dei Principi di Cattolica in Palermo. In 1733, he was appointed as an expert to resolve a dispute between the painters Venerando Costanza and Pietro Paolo Vasta, who were competing for the commission to decorate the Cathedral of Acireale. Borremans ruled in favor of Vasta. He himself was later involved in a similar competition with Olivio Sòzzi over the decoration of the Cathedral of Alcamo, ultimately securing the commission with the support of his patrons.

He also executed frescoes in the Church of Saint John the Apostle in Piazza Armerina, including a depiction of the Assumption of Mary.

In the final years of his life, Borremans reduced his artistic output, and fewer works are documented from this period. He died on 17 April 1744 and was buried in the Capuchin Church in Palermo.

Pieta (The Lamentation of Christ). Stone sculpture by an unknown artist. Now housed in the Diocesan Museum of Palermo (Museo Diocesano di Palermo). Second half of the 15th century.

Statue of St. Agatha used for processions. Paolo Amato (born in Cimmina) and an unknown Sicilian painter (c. 1680-1750).

Museo Diocesano di Palermo (MuDiPa)

St. Agatha: Detail of the processional cart (Museo Diocesano di Palermo)

St. Agatha: Detail of the processional cart (Museo Diocesano di Palermo)

Late 14th century tempera painting on wood by Jacopo di Michele, also called Jacopo Gera, Iacopo di Michele, or Gera da Pisa showing St. Anna, the Virgin and Child, St. John the Evangelist, and St. James the Apostle. Jacopo di Michele was active mainly in Pisa and other parts of Tuscany.

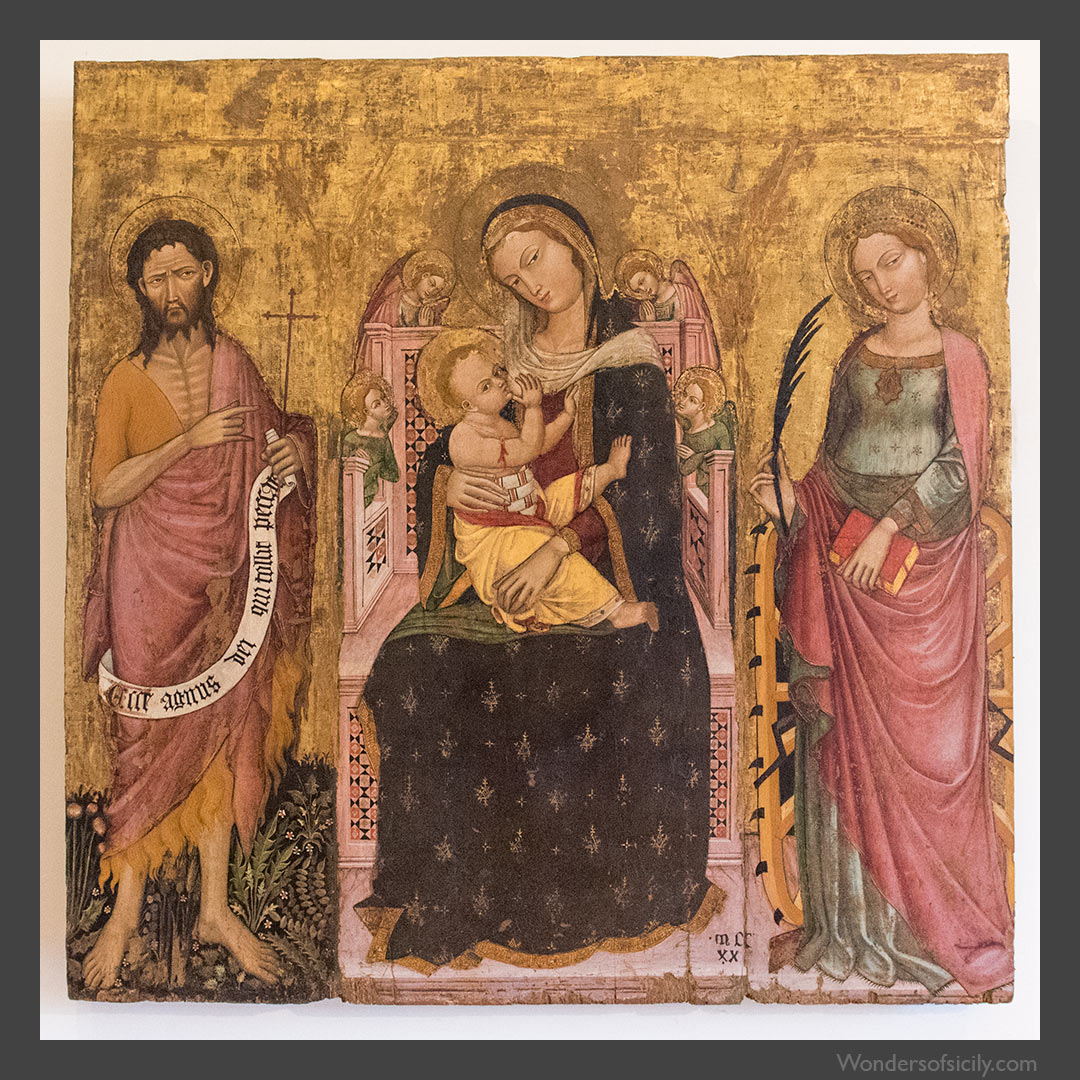

The Nursing Madonna (Maria Lactans – Maria delle Latte). On the left, John the Baptist; on the right, Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Unknown painter, tempera on wood. 1420. It once belonged to the Oratorio di S. Maria di Gesù nel piano S. Anna, Palermo, now in the Diocesan Museum in Palermo. The scroll John the Baptist is holding reads: “Ecce agnus dei qui tollit peccata mundi” (Latin for: “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.” It is a quote from the Gospel of John (John 1:29), traditionally attributed to John the Baptist, which aligns with the iconography in which he often holds or points to this phrase.

Early 16th-century Crucifix, housed in the Diocesan Museum of Palermo.