The Normans in Sicily

The term "Normans" (“men from the North”) applied first to the people of Scandinavia in general, and afterwards (Northmannus, Normannus, Normand) it is the name of the Viking colonists from Scandinavia who settled themselves in Gaul and founded Normandy. The Normans’ adopted a new religion (became Christians), a new language, a new system of law and society, new thoughts and feelings on all matters.

From their new home in northern France they set forth on new errands of conquest, chiefly in the British Islands and in southern Italy and Sicily.

If Britain and Sicily were the greatest fields of their enterprise, they were however very far from being the only fields. The same spirit of enterprise which brought the Northmen into Gaul seems to carry the Normans into every corner of the world. The conquest of England was made directly from Normandy, by the reigning duke, in a comparatively short time, while the conquest of Sicily grew out of the earlier and far more gradual conquest of Apulia and Calabria by private men, making their own fortunes and gathering round them followers from all quarters. They fought simply for their own hands, and took what they could by the right of the stronger.

They started with no such claim as Duke William put forth to justify his invasion of England; their only show of legal right was the papal grant of conquests that were already made. The conquest of Apulia, won bit by bit in many years of what we can only call freebooting, was not a national Norman enterprise like the conquest of England, and the settlement to which it led could not be a national Norman settlement in the same sense.

The Sicilian enterprise had in some respects another character. By the time it began the freebooters had grown into princes. Sicily was won by a duke of Apulia and a count of Sicily. Warfare in Sicily brought in higher motives and objects. Althought this was before the Crusades, the strife with the Muslims at once brought in the crusading element. Duke William was undisputed master of England at the end of five years; it took Count Roger thirty years to make himself undisputed master of Sicily. The one claimed an existing kingdom, and obtained full possession of it in a comparatively short time; the other formed for himself a dominion bit by bit, which rose to the rank of a kingdom.

Professor Robert Bartlett describes their exit like this in the excellent BBC documentary “The Normans”: “The Normans simply disappeared. This might sound like failure, but in fact it was the key to their success. They weren’t interested in the purity of their blood. They came, they saw, they conquered. Then they married the locals, learnt the language, and assimilated themselves out of existence.”

Links to more information about the Normans

- The Norman Conquest (Medievalsicily.com)

- Sicilian Peoples: The Normans by L. Mendola and V. Salerno (Bestofsicily.com)

- Tracing the Norman Rulers of Sicily by Louis Inturrisi (The New York Times)

The Normans in South Italy

999–1017 Arrival of the Normans in Italy

1009–1022 Lombard revolt

1022–1046 Mercenary service

1046–1059 County of Melfi

1049–1098 County of Aversa

1053–1105 Conquest of the Abruzzo

1061–1091 Conquest of Sicily

1073–1077 Conquest of Amalfi and Salerno

1059–1085 Byzantine-Norman wars

1077–1139 Conquest of Naples

1091: The county of Ragusa was founded in 1091 by Count Roger for his son, Godfrey.

1095: 22 December Roger II is born

1105: Roger II is named Count of Sicily

1127: Roger II becomes Duke of Apulia and Calabria

1130: Roger II becomes King of Sicily

1130s Cappella Palatina: Commenced by Roger II

1131 Building of the cathedral in Cefalù begins (Roger II)

1140 Cappella Palatina is consecrated.

c1140-c1147 The painted wooded ceiling in Cappella Palatina was completed

1143–1151 The mosaics in La Martorana (Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio) was made

1154: 26 February Roger II dies and William I becomes King of Sicily

1154-1166: The mosaics of the central nave of the Cefalù Cathedral and the nave and aisles of the Palatine Chapel (Cappella Palatina) were most likely made during the rule of William I

1160-70 c. Sala di Ruggero (King Roger's Room) in the Norman Palace is made

1166: 7 May King William I dies in Palermo

1174–1189 The cathedral in Monreale is built (King William II)

1194 Sicily falls into the hands of the Germanic Hohenstaufen dynasty

Christ Pantocrator in the Cefalù Cathedral.

The Normans in Sicily

“For the first, and indeed the last, time in European history, the three great civilizations of the Mediterranean, the Latin, the Greek and the Arabic all came together in harmony and concur. And all this occurred less than a hundred years after the schism between the Greek and the Latin churches, and in the very century of the second and third crusades, where just a few hundred miles to the East Christians and Muslims were bashing each other’s brains out. Only here, in this one island, in the dead centre of the Mediterranean, was there peace, understanding and mutual respect. Norman Sicily remains a lesson to us all.”

John Julius Norwich

See also: Conquest and Conversion in Medieval Muslim Sicily September 28, 2017 A talk by Alex Metcalfe, Senior Lecturer, Department of History, Lancaster University, UK.

Related links

- Depictions of Jesus (as Christ Pantocrator) in Sicily

- The Monreale Cathedral

- The Cefalù Cathedral

- Mosaics in Sicily

- Churches in Sicily

The Norman Rulers in Sicily

- Roger I (c. 1031–1101 Mileto), also known as Great Count Roger I, Roger Bosso, The Great Count. Italian: Ruggero I di Sicilia.

- Roger II (1095–1154)

Rogerios Rex (inscription in mosaic, Martorana, Palermo) - Simon of Hauteville (1093–1105), also known as Simon de Hauteville (in French) and Simone D'Altavilla (in Italian). He was the eldest son and successor of Roger I, count of Sicily, and Adelaide del Vasto.

- William I (1131–1166), also known as William the Bad or the Wicked

- William II (1155–1189), also known as William the Good

The Normans landed in Sicily as mercenaries in 1061. In 1194 Sicily fell into the hands of the Germanic Hohenstaufen dynasty

Byzantine mosaic of the coronation of Roger II in Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio

The Normans in Sicily: Roger II receiving the crown directly from Christ and not the Pope. Mosaic in the Martorana, Palermo. The mosaic carries an inscription Rogerios Rex in Greek letters. After the Sicilian Vespers of 1282 the island's nobility gathered in the church for a meeting that resulted in the Sicilian crown being offered to Peter III of Aragon.

Christ Pantocrator in Martorana (Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio), Palermo. The 12th century mosaics were executed by Byzantine craftsmen.

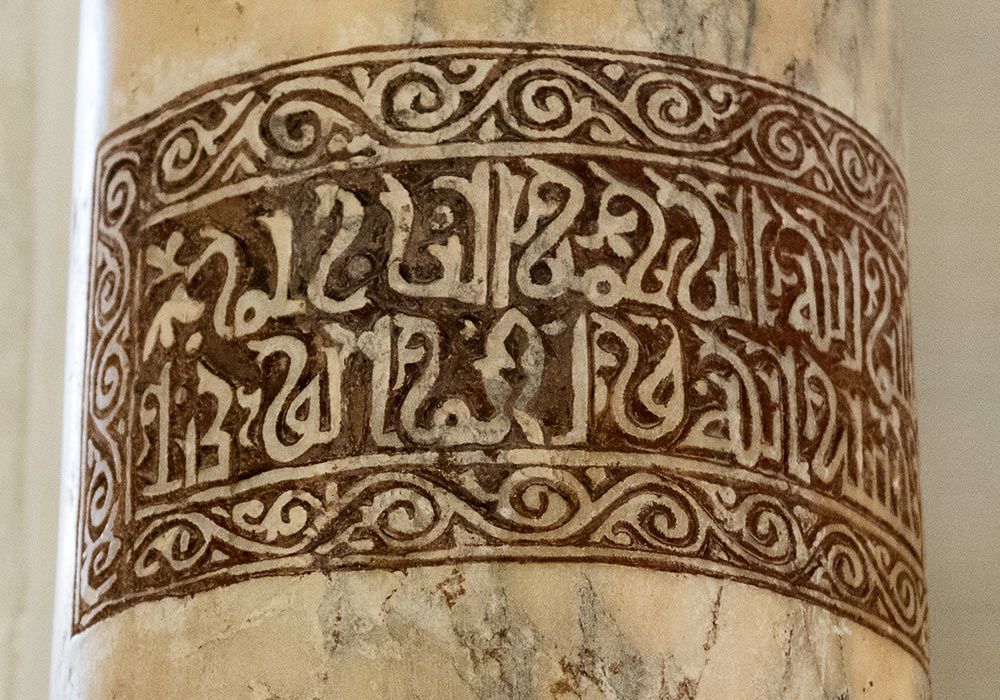

Islamic inscription on a column in La Martorana (Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio), Palermo. The inscription (in Kufic, the oldest calligraphic form of the various Arabic scripts) reads:

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate, ("Basmala" - all prayers and chapters in the Quran starts with these words)

God is sufficient for me and He is the best advocate

Norman Monuments in Sicily (selection)

- Castelvetrano

The little 12th Century church of the SS. Trinità di Delia is, according to John Julius Norwich "the perfect fusion of Arab and Byzantine". [Link to the church on Google Maps] - Cefalù Cathedral

"Though much of the inside is now distressingly baroque, the outside is exquisite and the great apse mosaic the most sublime masterpiece Sicily has to offer."

After Norwich's book was written, the "distressingly baroque" elements have been removed. - Forza d'Agrò

The Basilian church SS. Pietro e Paolo is situated a few kilometres outside Forza d'Agrò. The inscription over the west door dates it to 1171-72. The church was built in the 560, then it was destroyed by the Arabs and it was rebuilt in the 1117. The church was restored by the architect Gherardo il Franco in the 1172 because of an earthquake. - Monreale

Cathedral and cloister

Castellaccio (12th Century) on the summit of Monte Caputo - Palermo

The Palatine Chapel (In the Royal Palace, also known as the Norman Palace)

Sala di Ruggero (In the Royal Palace)

S. Maria dell' Ammariglio (the Martorana)

S. Giovanni degli Eremiti

S. Spirito (the church known for the Sicilian Vespers in 1282)

The Royal tombs of Roger II, Henry VI, Constance and Frederick II (in the Palermo Cathedral / Duomo)

Source: John Julius Norwich: The Normans in Sicily: The Magnificent Story of "the other Norman Conquest

Capital in the Monreale cathedral.

See more Sicilian capitals here

Facts about the Normans in Sicily

Unlike the Norman conquest of England (1066), which took a few years after one decisive battle, the conquest of southern Italy was the product of decades and a number of battles, few decisive. Many territories were conquered independently, and only later were unified into a single state. Compared to the conquest of England it was unplanned and disorganised, but equally complete.

The Norman conquest of Sicily left an indelible mark on the island's history. From Roger's initial campaigns to the ascension of Roger II as King of Sicily, the Normans brought stability and prosperity to the region.

Video: Vikings Heritage: The Splendour of Norman Sicily

The Normans arrive in Sicily

Monte Gargano, just east of Foggia, is the starting point for the Normans' adventure in Sicily. In 1016 about 40 Norman pilgrims met Melus, a noble Lombard from Bari who had been driven into exile by the Byzantines. Melus appealed to the pilgrims for help in ousting the Byzantines and in restoring the Roman Church throughout the southern part of the peninsula. The Normans returned the next year, and met Melus at Capua, north of Naples. Although defeated at first, the Normans continued to plunder, and in 1038 the Greeks and their Norman allies landed on Sicilian soil. Messina fell at once, and then Syracuse.

Coins from the Norman period. (Mandralisca Museum, Cefalù)

Coronation mantle made for Roger II

Coronation mantle made for Roger II in 1133/34 in the royal workshop in Palermo of fabric from Byzantium or Thebes, Samite, silk, gold, pearls, filigree, sapphires, garnets, glass, and cloisonné enamel.

Arab-Norman bronze pail (c. 1100-1200) from the Contrada Bambina shipwreck near Marsala. Beneath the rim, a punched inscription from the Qur'an in early Arabic characters. This pail was part of the exhibition Storms, War and Shipwrecks: Treasures from the Sicilian Seas (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 21 Jun 2016 to 25 Sep 2016), but is owned by Museo archeologico regionale Lilibeo-Baglio Anselmi, Marsala.

The Normans’ use of bilingual documents

To understand why the Normans used bilingual documents, one should consider how this made the documents more credible and stand out with authority. Alex Metcalfe writes:

“Back in the 1090s, it is only with the benefit of hindsight that we can imagine why bilingual records were issued. Certainly, in a breeding-ground for dubious diplomata and false claims, there was an urgent need for new comital documents whose distinctive features, both literal and visual, underwrote their credibility and authority. In this respect, Arabic-Greek documents provided a double form of validation that was irreplicable without the input of two, trained, non-‘Latin’ scribes. It is not coincidental that this period of nascent bureaucracy saw the rise of ‘Greek’ scribes, functionaries and locals with various titles – some more vague than others. Greek was the Norman rulers’ prevailing written language of choice, and it appeared in a range of administrative contexts especially in the first half of the 1100s.” (Alex Metcalfe: Language and the written record: loss, survival and revival in early Norman Sicily in Multilingual and multigraphic manuscripts and documents of East and West, eds. Giuseppe Mandalà and Inmaculada Pérez Martín (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2014))

Norman Castles in Sicily

The list is made by Christopher Gravett and is published in Norman Stone Castles (2) (Fortress) . Osprey Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Aci Castello (prov. Catania)

The castle, of black lavastone, sits on a spur overlooking the sea on a site that had been fortified since the Roman period. It was rebuilt by Tancred in 1189.

Adrano (prov. Catania)

This is an early, square donjon surrounded by a later low chemise wall with circular corner towers. Other elements of the castle complex are of later date.

Caccamo (prov. Palermo)

The castle is perched high on a ridge of Mount Calogero, about 14km from Termini Imerese, south-west of Cefalù. It was built by a rich Norman called Matthew Bonnellus. The castle has been much rebuilt and restored.

Calascibetta (prov. Enna)

The town is some 6km to the north of Enna, and lies at a quota of 691m in the Erei mountains. The town’s name is of Arabic origin (Kalat-Scibet), and means ‘the castle on the summit’. In 1062 Count Roger built a castle and church here.

Caltabellotta (prov. Agrigento)

The site has a single Norman tower surviving which stands on a hill at an altitude of 950m. The castle was built on the site of a former Arab castle. It was here in 1194 that the widow Sybil took refuge together with her son William III from the pursuit of the Swabian emperor Henry VI.

Lentini (prov. Siracusa)

The town lies at a height of 56m, and is some 45km from the provincial capital Siracusa. The Arabs fortified the town, before it fell to the Normans. The town suffered earthquakes in 1140 and l169, which destroyed many buildings of the period. The site of the castle was overlaid by Frederick II.

Mazara del Vallo (prov. Trapani)

The town is on the west coast of Sicily, some 40km south of Trapani. The site was fortified by Roger I in 1072–73, to protect against the Saracen invasions. The first Sicilian parliament was held here soon after. Only its double-arched entrance remains, near Piazza Makara.

Milazzo (prov. Messina)

The city lies 40km west of Messina. The oldest part of the site is the ‘Mastio’, which is known as the ‘Saracen Tower’. The castle was heavily reworked in 1240 by Richard of Lentini for Frederick II.

Palermo: Castellaccio

Perched on Monte Caputo, and built in the second half of the 12th century, the site forms a large irregular rectangle, with rectangular towers. The ground plan of a square donjon with a dividing wall still exists.

Palermo: La Cuba

This palace-tower was built by King William II in 1180, and was set in a large park, which also contained another building, ‘La Cubula’ (see below). It now stands in the grounds of the Villa di Napoli, on Corso Calatafimi, through which access is gained.

Palermo: La Cubula

The building is located on Corso Calatafimi, near to La Cuba: once again, access is via Villa di Napoli.

Palermo: La Ziza

La Ziza lies in the north-west part of the Sicilian capital in Piazza Guglielmo il Buono, near Porta Nuova. It was begun by William I in about 1162, and was completed by his son, William II. Today it contains a museum of Islamic art.

Palermo: Palazzo Conte Federico

Via dei Biscottari. Arab-Norman work survives in the tower of this palazzo, called the ‘Scrigno Tower’: it is now a private building.

Paternò (prov. Catania)

Located 13km from Catania, the lavastone castle, which dominates the town, was built by Roger I in 1073 and rebuilt in the 14th century. It has been much restored in recent years. The castle is open to visitors daily.

Termini Imerese (prov. Palermo)

The castle lies in the upper part of this thermal spa town, which is 36km from Palermo. The site is an ancient one, stretching back to classical times, and its use was continued by the Normans following their takeover in the 13th century. The castle was overlaid by Frederick II.

Trapani (provincial capital)

The castle lies on an ancient site on the summit of Mt Erice, and provides excellent views down over the city. In the 12th century the Normans used materials from existing structures to build a castle and curtain wall with numerous entrances and gates. The original site, more extensive than today’s remains indicate, contained an outer ditch with three towers in advanced positions: this area was connected to the main castle via a drawbridge.

Gravett, Christopher. Norman Stone Castles (2) (Fortress) . Osprey Publishing. Kindle Edition.